Open-source projects have a life-cycle. They are born because a problem needs to be solved. You start building an initial solution, improve it, fix bugs, and incorporate feedback. Some projects become successful. Their use case is broad enough to attract a large user base and a sufficient number of maintainers that keep the software going.

Others don’t. They never gain traction, and eventually, they die. The reasons for a project to fail are manifold. They address a problem space that is too narrow in scope, the solution does not apply to the problem, or they are just not built very well.

Admitting that a project should be retired is hard. Hours of work go into a project during its early days. Retiring a software project often feels a bit like giving up on your child. Finding the right time to sunset a project seems hard as well – after all, it’s out there, and someone might be using it – but the signals are easy to spot:

Few people create tickets. Every software has bugs. When developers actively use your project, they find bugs and submit reports. When you never receive a bug report or support question, you either wrote the world’s first and only completely bug-free software, or it is not actively used.

Few people are following the project. I like Github’s watch feature. Not because I need the attention but because it is an indicator of how many people consider your project useful enough that they want to stay in the loop about every pull request — even the ones that just correct a typo in the README. If you’re lucky enough to be able to open-source software as part of your job and you create the library under the organisation you’ve worked for, then your project has a bunch of followers from the start. If you go back years after the project has been created and the only people watching the repository are former co-workers, it’s time to face it: Nobody has an interest in your project.

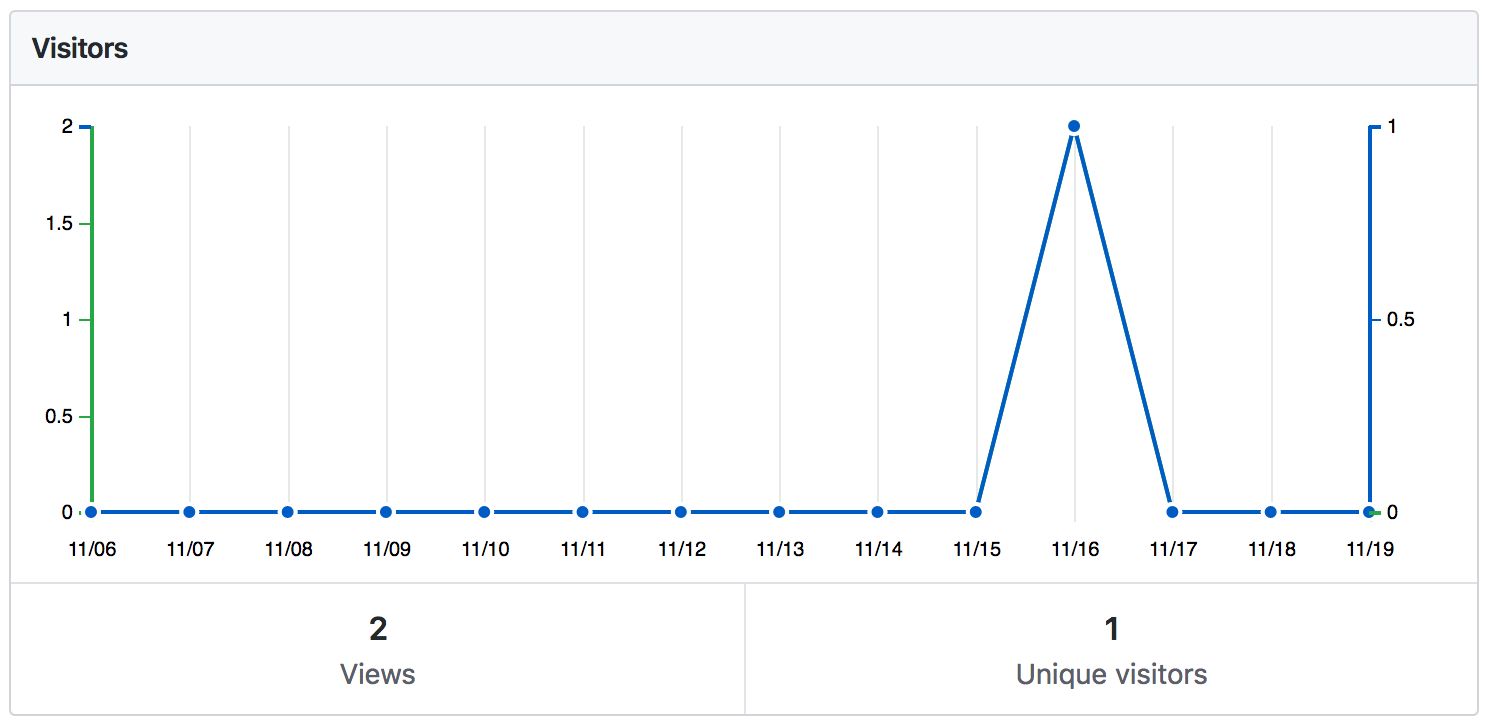

Few people are visiting the project. It’s pretty obvious — if no-one visits the web site for your project, no-one uses your project. If the visitor graph for your project looks like the one below, the project is pretty much dead. Chances are, the only visitor was you.

- Few projects depend on the library. Open-source projects start because there is a need or a problem to be solved. Often when we build something, encounter a problem, and develop a solution that is worth breaking out into a generic library because the solution could be useful to other developers. That original project usually is the new library’s first dependent. Successful libraries grow their number of dependents over time — an indication that it solves a universal problem. If your project has only a handful dependents and most of them are unmaintained side projects you started four years ago while your wife was on a three-week business trip, then you have solved a problem only you have.

In that light, it’s time for me to sunset django-skivvy. I wrote the library a few years back during my stint at Cadasta to simplify how we write tests for Django views and to remove repeated boilerplate code. The only project that ever used the library is the Cadasta Platform, which has been on its way out for a while now. The only people who ever filed tickets where Cadasta employees at the time. No-one is visiting the repo, no-one, who hasn’t worked at Cadasta, is watching it, and I can’t even remember the last time someone starred the project. django-skivvy is not in use and investing more time to provide even the most basic maintenance, such as making sure it still works with newer versions of Django, is not worth it.